21 Testing

For simple apps, it’s easy enough to remember how the app is supposed to work, so that when you make changes to add new features, you don’t accidentally break existing capabilities. However, as your app gets more complicated it becomes impossible to hold it all in your head simultaneously. Testing is a way to capture desired behaviour of your code, in such a way that you can automatically verify that it keeps working the way you expect. Turning your existing informal tests into code is painful when you first do it, because you need to carefully turn every key press and mouse click into a line of code, but once done, it’s tremendously faster to re-run your tests.

We’ll perform automated testing with the testthat package. testthat requires turning your app into a package, but as discussed in Chapter 20, this is not too much work, and I think pays off for other reasons.

A testthat test looks like this:

We’ll come back to the details very soon, but note that a test starts by declaring the intent (“as.vector() strips names”) then uses regular R code to generate some test data. The test data is then compared to the expected result using a expectation, a function that starts with expect_. The first argument is some code to run, and the second argument describes the expected result: here we verify that the output of as.vector(x) equals c(1, 2).

We’ll work through four levels of testing in this chapter:

We’ll start by testing non-reactive functions. This will help you learn the basic testing workflow, and allow you to verify the behaviour of code that you’ve extracted out of the server function or UI. This is exactly the same type of testing you’d do if you were writing a package, so you can find more details in the testing chapter of R Packages.

Next you’ll learn how to test the flow of reactivity within your server function. You’ll set the value of inputs and then verify that reactives and outputs have the values you expect.

Then we’ll test parts of Shiny that use JavaScript (e.g. the

update*functions) by running the app in a background web browser. This is a high fidelity simulation because it runs a real browser, but on the downside, the tests are slower to run and you can no longer so easily peek inside the app.Finally, we’ll test app visuals by saving screenshots of selected elements. This is necessary for testing app layout, CSS, plots, and HTML widgets, but is fragile because screenshots can easily change for many reasons. This means that human intervention is required to confirm whether each change is OK or not, making this the most labour intensive form of testing.

These levels of testing form a natural hierarchy because each technique provides a fuller simulation of the user experience of an app. The downside of the better simulations is that each level is slower because it has to do more, and more fragile because more external forces come into play. You should always strive to work at the lowest possible level so your tests are as fast and robust as possible. Over time this will also influence the way you write code: knowing what sort of code is easier to test will naturally push you towards simpler designs. Interleaved between the different levels of testing, I’ll also provide advice about testing workflow and more general testing philosophy.

library(shiny)

library(testthat) # >= 3.0.0

library(shinytest)

#> shinytest requires PhantomJS to record and run tests.

#> • To install it, run shinytest::installDependencies()

#> • If it is installed, please check it is available on the PATH

#> IMPORTANT! shinytest is deprecated and may not work with shiny>1.8.1.1.

#> Please switch to shinytest2.

#> See https://rstudio.github.io/shinytest2/articles/z-migration.html21.1 Testing functions

The easiest part of your app to test is the part that has the least to do with Shiny: the functions extracted out of your UI and server code as described in Chapter 18. We’ll start by discussing how to test these non-reactive functions, showing you the basic structure of unit testing with testthat.

21.1.1 Basic structure

Tests are organised into three levels:

File. All test files live in

tests/testthat, and each test file should correspond to a code file inR/, e.g. the code inR/module.Rshould be tested by the code intests/testthat/test-module.R. Fortunately you don’t have to remember that convention: just useusethis::use_test()to automatically create or locate the test file corresponding to the currently open R file.Test. Each file is broken down into tests, i.e. a call to

test_that(). A test should generally check a single property of a function. It’s hard to describe exactly what this means, but a good heuristic is that you can easily describe the test in the first argument totest_that().Expectation. Each test contains one or more expectations, with functions that start with

expect_. These define exactly what you expect code to do, whether it’s returning a specific value, throwing an error, or something else. In this chapter, I’ll discuss the most important expectations for Shiny apps but you can see the full list on the testthat website.

The art of testing is figuring out how to write tests that clearly define the expected behaviour of your function, without depending on incidental details that might change in the future.

21.1.2 Basic workflow

Now you understand the basic structure, lets dive into some examples.

I’m going to start with a simple example from Section 18.3.1.

Here I’ve extracted out some code from my server function, and called it load_file():

load_file <- function(name, path) {

ext <- tools::file_ext(name)

switch(ext,

csv = vroom::vroom(path, delim = ",", col_types = list()),

tsv = vroom::vroom(path, delim = "\t", col_types = list()),

validate("Invalid file; Please upload a .csv or .tsv file")

)

}For the sake of this example I’m going to pretend this code lives in R/load.R, so my tests for it need to live in tests/testthat/test-load.R.

The easiest way to create that file is to run usethis::use_test() with load.R 61.

There are three main things that I want to test for this function: can it load a csv file, can it load a tsv file, and does it give an error message for other types? To test those three things I’ll need some sample files, which I save in the session temp directory so they’re automatically cleaned up after my tests are run. Then I write three expectations, two checking that the loaded file equals the original data, and one checking that I get an error.

test_that("load_file() handles all input types", {

# Create sample data

df <- tibble::tibble(x = 1, y = 2)

path_csv <- tempfile()

path_tsv <- tempfile()

write.csv(df, path_csv, row.names = FALSE)

write.table(df, path_tsv, sep = "\t", row.names = FALSE)

expect_equal(load_file("test.csv", path_csv), df)

expect_equal(load_file("test.tsv", path_tsv), df)

expect_error(load_file("blah", path_csv), "Invalid file")

})

#> Test passed with 3 successes 🥳.There are four ways to run this test:

As I’m developing it, I run each line interactively at the console. When an expectation fails, it turns into an error, which I then fix.

Once I’ve finished developing it, I run the whole test block. If the test passes, I get a message like

Test passed 😀. If it fails, I get the details of what went wrong.As I develop more tests, I run all of the tests for the current file62 with

devtools::test_file(). Because I do this so often, I have a special keyboard shortcut set up to make it as easy as possible. I’ll show you how to set that up yourself very shortly.Every now and then I run all of the tests for the whole package with

devtools::test(). This ensures that I haven’t accidentally broken anything outside of the current file.

21.1.3 Key expectations

There are two expectations that you’ll use a lot of the time when testing functions: expect_equal() and expect_error().

Like all expectation functions the first argument is the code to check and the second argument is the expected outcome: an expected value in the case of expect_equal() and expected error text in the case of expect_error().

To get a sense for how these functions work, it’s useful to call them directly, outside of tests.

When using expect_equal() remember that you don’t have to test that whole object: generally it’s better to test just the component that you’re interested in:

complicated_object <- list(

x = list(mtcars, iris),

y = 10

)

expect_equal(complicated_object$y, 10)There are a few expectations for special cases of expect_equal() that can save you a little typing

expect_true(x)andexpect_false(x)are equivalent toexpect_equal(x, FALSE)andexpect_equal(x, TRUE).expect_null(x)is equivalent toexpect_equal(x, NULL).expect_named(x, c("a", "b", "c"))is equivalent toexpect_equal(names(x), c("a", "b", "c")), but has optionsignore.orderandignore.case.expect_length(x, 10)is equivalent toexpect_equal(length(x), 10).

There are also functions that implement relaxed versions of expect_equal() for vectors:

expect_setequal(x, y)tests that every value inxoccurs iny, and every value inyoccurs inx.expect_mapequal(x, y)tests thatxandyhave the same names and thatx[names(y)]equalsy.

It’s often important to test that code generates an error, for which you can use expect_error():

expect_error("Hi!")

#> Error:

#> ! Expected "Hi!" to throw a error.

expect_error(stop("Bye"))Note that the second argument to expect_error() is a regular expression — the goal is to find a short fragment of text that matches the error you expect and is unlikely to match errors that you don’t expect.

f <- function() {

stop("Calculation failed [location 1]")

}

expect_error(f(), "Calculation failed [location 1]")

#> Error in `f()`:

#> ! Calculation failed [location 1]

expect_error(f(), "Calculation failed \\[location 1\\]")But it’s better still to just pick a small fragment to match:

expect_error(f(), "Calculation failed")Or use expect_snapshot(), which we’ll discuss shortly.

expect_error() also comes with variants expect_warning() and expect_message() for testing for warnings and messages in the same way as errors.

These are rarely needed for testing Shiny apps but are very useful for testing packages.

21.1.4 User interface functions

You can use the same basic idea to test functions that you’ve extracted out of your UI code. But these require a new expectation, because manually typing out all the HTML would be tedious, so instead we use a snapshot test63. A snapshot expectation differs from other expectations primarily in that the expected result is stored in a separate snapshot file, rather than in the code itself. Snapshot tests are most useful when you are designing complex user interface design systems, which is outside of the scope of most apps. So here I’ll briefly show you the key ideas, and then point you to additional resources to learn more.

Take this UI function we defined earlier:

sliderInput01 <- function(id) {

sliderInput(id, label = id, min = 0, max = 1, value = 0.5, step = 0.1)

}

cat(as.character(sliderInput01("x")))

#> <div class="form-group shiny-input-container">

#> <label class="control-label" id="x-label" for="x">x</label>

#> <input class="js-range-slider" id="x" data-skin="shiny" data-min="0" data-max="1" data-from="0.5" data-step="0.1" data-grid="true" data-grid-num="10" data-grid-snap="false" data-prettify-separator="," data-prettify-enabled="true" data-keyboard="true" data-data-type="number"/>

#> </div>How would we test that this output is as we expect?

We could use expect_equal():

test_that("sliderInput01() creates expected HTML", {

expect_equal(as.character(sliderInput01("x")), "<div class=\"form-group shiny-input-container\">\n <label class=\"control-label\" id=\"x-label\" for=\"x\">x</label>\n <input class=\"js-range-slider\" id=\"x\" data-skin=\"shiny\" data-min=\"0\" data-max=\"1\" data-from=\"0.5\" data-step=\"0.1\" data-grid=\"true\" data-grid-num=\"10\" data-grid-snap=\"false\" data-prettify-separator=\",\" data-prettify-enabled=\"true\" data-keyboard=\"true\" data-data-type=\"number\"/>\n</div>")

})

#> Test passed with 1 success 🌈.But the presence of quotes and newlines requires a lot of escaping in the string — that makes it hard to see exactly what we expect, and if the output changes, makes it hard to see exactly what’s happened.

The key idea of snapshot tests is to store the expected results in a separate file: that keeps bulky data out of your test code, and means that you don’t need to worry about escaping special values in a string.

Here we use expect_snapshot() to capture the output displayed on the console:

test_that("sliderInput01() creates expected HTML", {

expect_snapshot(sliderInput01("x"))

})The main difference with other expectations is that there’s no second argument that describes what you expect to see.

Instead, that data is saved in separate .md file.

If your code is in R/slider.R and your test is in tests/testthat/test-slider.R, then snapshot will be saved in tests/testhat/_snaps/slider.md.

The first time you run the test, expect_snapshot() will automatically create the reference output, which will look like this:

# sliderInput01() creates expected HTML

Code

sliderInput01("x")

Output

<div class="form-group shiny-input-container">

<label class="control-label" id="x-label" for="x">x</label>

<input class="js-range-slider" id="x" data-skin="shiny" data-min="0" data-max="1" data-from="0.5" data-step="0.1" data-grid="true" data-grid-num="10" data-grid-snap="false" data-prettify-separator="," data-prettify-enabled="true" data-keyboard="true" data-data-type="number"/>

</div>If the output later changes, the test will fail.

You either need to fix the bug that causes it to fail, or if it’s a deliberate change, update the snapshot by running testthat::snapshot_accept().

It’s worth contemplating the output here before committing to this as a test. What are you really testing here? If you look at how the inputs become the outputs you’ll notice that most of the output is generated by Shiny and only a very small amount is the result of your code. That suggests this test isn’t particularly useful: if this output changes, it’s much more likely to be the result of change to Shiny than the result of a change to your code. This makes the test fragile; if it fails it’s unlikely to be your fault, and fixing the failure is unlikely to be within your control.

You can learn more about snapshot tests at https://testthat.r-lib.org/articles/snapshotting.html.

21.2 Workflow

Before we talk about testing functions that use reactivity or JavaScript, we’ll take a brief digression to work on your workflow.

21.2.1 Code coverage

It’s very useful to verify that your tests test what you think they’re testing. A great way to do this is with “code coverage” which runs your tests and tracks every line of code that is run. You can then look at the results to see which lines of your code are never touched by a test, and gives you the opportunity to reflect on if you’ve tested the most important, highest risk, or hardest to program parts of your code. It’s not a substitute for thinking about your code — you can have 100% test coverage and still have bugs. But it’s a fun and a useful tool to help you think about what’s important, particularly when you have complex nested code.

Won’t cover in detail here, but I highly recommend trying it out with devtools::test_coverage() or devtools::test_coverage_file().

The main thing to notice is that green lines are tested; red lines are not.

Code coverage supports a slightly different workflow:

Use

test_coverage()ortest_coverage_file()to see which lines of code are tested.Look at untested lines and design tests specifically to test them.

Repeat until all important lines of code are tested. (Getting to 100% test coverage often isn’t worth it, but you should check that you are hitting the most critical parts of your app)

Code coverage also works with the tools for testing reactivity and (to some extent) JavaScript, so it’s a useful foundational skill.

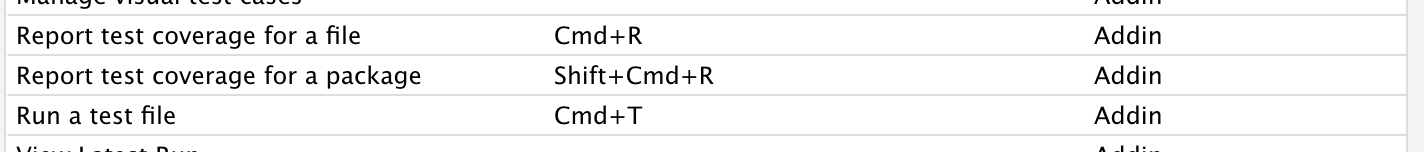

21.2.2 Keyboard shortcuts

If you followed the advice in Section 20.2 then you can already run tests just by typing test() or test_file() at the console.

But tests are something that you’ll do so often it’s worth having a keyboard shortcut at your fingertips.

RStudio has one useful shortcut built in: Cmd/Ctrl + Shift + T runs devtools::test().

I recommend that you add three yourself to complete the set:

Bind Cmd/Ctrl + T to

devtools::test_file()Bind Cmd/Ctrl + Shift + R to

devtools::test_coverage()Bind Cmd/Ctrl + R to

devtools::test_coverage_file()

You’re of course free to choose whatever shortcut makes sense to you, but these have share some underlying structure. Keyboard shortcuts using Shift apply to the whole package, and without shift apply to the current file.

Figure 21.1 shows what my keyboard shortcuts look like on a Mac.

Figure 21.1: My keyboard shortcut for a Mac.

21.2.3 Workflow summary

Here’s a summary of all the techniques I’ve talked about so far:

From the R file, use

usethis::use_test()to create the test file (the first time it’s run) or navigate to the test file (if it already exists).Write code/write tests. Press

cmd/ctrl + Tto run the tests and review the results in the console. Iterate as needed.If you encounter a new bug, start by capturing the bad behaviour in a test. In the course of making the minimal code, you’ll often get a better understanding of where the bug lies, and having the test will ensure that you can’t fool yourself into thinking that you’ve fixed the bug when you haven’t.

Press

ctrl/cmd + Rto check that you’re testing what you think you’re testingPress

ctrl/cmd + shift + Tto make you have accidentally broken anything else.

21.3 Testing reactivity

Now that you understand how to test regular, non-reactive code, it’s time to move on to challenges specific to Shiny. The first challenge is testing reactivity. As you’ve already seen, you can’t run reactive code interactively:

x <- reactive(input$y + input$z)

x()

#> Error in `.getReactiveEnvironment()$currentContext()`:

#> ! Operation not allowed without an active reactive context.

#> • You tried to do something that can only be done from inside a reactive consumer.You might wonder about using reactiveConsole() like we did in Chapter 15.

Unfortunately its simulation of reactivity depends fundamentally on an interactive console, so won’t work in tests.

Not only does the reactive error when we attempt to evaluate it, even if it did work input$y and input$z wouldn’t be defined.

To see how it works, let’s start with a simple app that has three inputs, one output, and three reactives:

ui <- fluidPage(

numericInput("x", "x", 0),

numericInput("y", "y", 1),

numericInput("z", "z", 2),

textOutput("out")

)

server <- function(input, output, session) {

xy <- reactive(input$x - input$y)

yz <- reactive(input$z + input$y)

xyz <- reactive(xy() * yz())

output$out <- renderText(paste0("Result: ", xyz()))

}To test this code we’ll use the testServer().

This function takes two arguments: a server function and some code to run.

The code is run in a special environment, inside the server function, so you can access outputs, reactives, and a special session object that allows you to simulate user interaction.

The main time you’ll use this is for session$setInputs() which allows you to set the value of input controls, as if you were a user interacting with the app in a browser.

testServer(server, {

session$setInputs(x = 1, y = 1, z = 1)

print(xy())

print(output$out)

})

#> [1] 0

#> [1] "Result: 0"(You can abuse testServer() to get in an interactive environment that does support reactivity: testServer(myApp(), browser()))

Note that we’re only testing the server function; the ui component of the app is completely ignored.

You can see this most clearly by inspecting the inputs: unlike a real Shiny app, all inputs start as NULL, because the initial value is recorded in the ui.

We’ll come back to UI testing in Section 21.4.

testServer(server, {

print(input$x)

})

#> NULLNow that you have a way to run code in a reactive environment you can combine it with what you already know about testing code to create something like this:

test_that("reactives and output updates", {

testServer(server, {

session$setInputs(x = 1, y = 1, z = 1)

expect_equal(xy(), 0)

expect_equal(yz(), 2)

expect_equal(output$out, "Result: 0")

})

})

#> Test passed with 3 successes 🌈.Once you’ve mastered the use of testServer(), then testing reactive code becomes almost as easy as testing non-reactive code.

The main challenging is debugging failing tests: you can’t step through them line-by-line like a regular test, so you’ll need to add a browser() inside of testServer() so that you can interactively experiment to diagnose the problem.

21.3.1 Modules

You can test a module in a similar way to testing an app function, but here it’s a little more clear that you’re only testing the server side of the module. Let’s start with a simple module that uses three outputs to display a brief summary of a variable:

summaryUI <- function(id) {

tagList(

outputText(ns(id, "min")),

outputText(ns(id, "mean")),

outputText(ns(id, "max")),

)

}

summaryServer <- function(id, var) {

stopifnot(is.reactive(var))

moduleServer(id, function(input, output, session) {

range_val <- reactive(range(var(), na.rm = TRUE))

output$min <- renderText(range_val()[[1]])

output$max <- renderText(range_val()[[2]])

output$mean <- renderText(mean(var()))

})

}We’ll use testServer() as above, but the call is a little different.

As before the first argument is the server function (now the the module server), but now we also need to supply additional arguments in a list called args.

This takes a list of arguments to the module server (the id argument is optional; testServer() will fill it in automatically if omitted).

Then we finish up with the code to run:

x <- reactiveVal(1:10)

testServer(summaryServer, args = list(var = x), {

print(range_val())

print(output$min)

})

#> [1] 1 10

#> [1] "1"Again, we can turn this into an automated test by putting it inside test_that() and calling some expect_ functions.

Here I wrap it all up into a test that checks that the module responds correctly as the reactive input changes:

test_that("output updates when reactive input changes", {

x <- reactiveVal()

testServer(summaryServer, args = list(var = x), {

x(1:10)

session$flushReact()

expect_equal(range_val(), c(1, 10))

expect_equal(output$mean, "5.5")

x(10:20)

session$flushReact()

expect_equal(range_val(), c(10, 20))

expect_equal(output$min, "10")

})

})

#> Test passed with 4 successes 😀.There’s one important trick here: because x is created outside of testServer(), changing x does not automatically update the reactive graph, so we have to do so manually by calling session$flushReact().

If your module has a return value (a reactive or list of reactives), you can capture it with session$getReturned().

Then you can check the value of that reactive, just like any other reactive.

datasetServer <- function(id) {

moduleServer(id, function(input, output, session) {

reactive(get(input$dataset, "package:datasets"))

})

}

test_that("can find dataset", {

testServer(datasetServer, {

dataset <- session$getReturned()

session$setInputs(dataset = "mtcars")

expect_equal(dataset(), mtcars)

session$setInputs(dataset = "iris")

expect_equal(dataset(), iris)

})

})

#> Test passed with 2 successes 🌈.Do we need to test what happens if input$dataset isn’t a dataset?

In this case, we don’t because we know that the module UI restricts the options to valid choices.

That’s not obvious from inspection of the server function alone.

21.3.2 Limitations

testServer() is a simulation of your app.

The simulation is useful because it lets you quickly test reactive code, but it is not complete.

Unlike the real world, time does not advance automatically. So if you want to test code that relies on

reactiveTimer()orinvalidateLater(), you’ll need to manually advance time by callingsession$elapse(millis = 300).testServer()ignores UI. That means inputs don’t get default values, and no JavaScript works. Most importantly this means that you can’t test theupdate*functions, because they work by sending JavaScript to the browser to simulates user interactions. You’ll require the next technique to test such code.

21.4 Testing JavaScript

testServer() is only a limited simulation of the full Shiny app, so that any code that relies of a “real” browser running will not work.

Most importantly, this means that no JavaScript will be run.

This might not seem important because we haven’t talked about JavaScript in this book, but there are a number of important Shiny functions that use it behind the scenes:

All

update*()functions, Section 10.1.showNotification()/removeNotification(), Section 8.2.showModal()/hideModal(), Section 8.4.1.insertUI()/removeUI()/appendTab()/insertTab()/removeTab(), which we’ll cover later in the book.

To test these functions you need to run the Shiny app in a real browser.

You could of course do this yourself using runApp() and clicking around, but we want to automate that process so that you run your tests frequently.

We’ll do this with an off-label use of the shinytest package.

You can use shinytest as the website recommends, automatically generating test code using an app, but since you’re already familiar with testthat, we’ll take a different approach, constructing tests by hand.

We’ll work with one R6 object from the shinytest package: ShinyDriver.

Creating a new ShinyDriver instance starts a new R process that runs your Shiny app and a headless browser.

A headless browser works just like a usual browser, but it doesn’t have a window that you can interact it; the sole means of interaction is via code.

The primary downsides of this technique is that’s slower than the other approaches (it takes at least a second for even the simplest apps), and you can only test the outside of the app (i.e. it’s harder to see the values of reactive variables).

21.4.1 Basic operation

To demonstrate the basic operation I’ll create a very simple app that greets you by name and provides a reset button.

ui <- fluidPage(

textInput("name", "What's your name"),

textOutput("greeting"),

actionButton("reset", "Reset")

)

server <- function(input, output, session) {

output$greeting <- renderText({

req(input$name)

paste0("Hi ", input$name)

})

observeEvent(input$reset, updateTextInput(session, "name", value = ""))

}To use shinytest you start an app with app <- ShinyDriver$new(), interact with it using app$setInputs() and friends, then get values returned by app$getValue():

app <- shinytest::ShinyDriver$new(shinyApp(ui, server))

app$setInputs(name = "Hadley")

app$getValue("greeting")

#> [1] "Hi Hadley"

app$click("reset")

app$getValue("greeting")

#> [1] ""Every use of shinytest begins by creating a ShinyDriver object with ShinyDriver$new(), which takes a Shiny app object or a path to a Shiny app.

It returns an R6 object that you interact with much like the session object you encountered above, using app$setInputs() — it takes a set of name-value pairs, updates the controls in the browser, and then waits until all reactive updates are complete.

The first difference is that you’ll need to explicitly retrieve values using app$getValue(name).

Unlike with testServer(), you can’t access the values of reactives using ShinyDriver because it can only see what a user of the app can see.

But there’s a special Shiny function called exportTestValues() that creates a special output that shinytest can see but a human cannot.

There are two other methods that allow you to simulate other actions:

app$click(name)clicks a button calledname.app$sendKeys(name, keys)sends key presses to an input control calledname.keyswill normally be string likeapp$sendKeys(id, "Hi!"). But you can also send special keys usingwebdriver::key, a laapp$sendKeys(id, c(webdriver::key$control, "x")). Note that any modifier keys will be applied to all subsequent key presses, so you’ll need multiple calls if you want some key presses with modifiers and some without.

See ?ShinyDriver for more details, and a list of more esoteric methods.

As before, once you’ve figured out the appropriate sequence of actions interactively, you can turn it into a test by wrapping in test_that() and calling expectations:

test_that("can set and reset name", {

app <- shinytest::ShinyDriver$new(shinyApp(ui, server))

app$setInputs(name = "Hadley")

expect_equal(app$getValue("greeting"), "Hi Hadley")

app$click("reset")

expect_equal(app$getValue("greeting"), "")

})The background Shiny app and web browser are automatically shut down when the app object is deleted and collected by the garbage collector.

If you’re not familiar with what that means, you might find https://adv-r.hadley.nz/names-values.html#gc helpful.

21.4.2 Case study

We’ll finish up with a case study exploring how you might test a more realistic example, combining both testServer() and shinytest.

We’ll use a radio-button control that also provides a free-text “other” option.

This might look familiar, as we used it before as a motivation for developing a module in 19.4.1.

ui <- fluidPage(

radioButtons("fruit", "What's your favourite fruit?",

choiceNames = list(

"apple",

"pear",

textInput("other", label = NULL, placeholder = "Other")

),

choiceValues = c("apple", "pear", "other")

),

textOutput("value")

)

server <- function(input, output, session) {

observeEvent(input$other, ignoreInit = TRUE, {

updateRadioButtons(session, "fruit", selected = "other")

})

output$value <- renderText({

if (input$fruit == "other") {

req(input$other)

input$other

} else {

input$fruit

}

})

}The actual computation is quite simple.

We could consider pulling the renderText() expression out into its own function:

other_value <- function(fruit, other) {

if (fruit == "other") {

other

} else {

fruit

}

}But I don’t think it’s worth it because the logic here is very simple and not generalisable to other situations. I think the net effect of pulling this code out of the app into a separate file would be make the code harder to read.

So we’ll start by testing the basic flow of reactivity: do we get the correct value after setting fruit to an existing option?

And do we get the correct value after setting fruit to other and adding some free text?

test_that("returns other value when primary is other", {

testServer(server, {

session$setInputs(fruit = "apple")

expect_equal(output$value, "apple")

session$setInputs(fruit = "other", other = "orange")

expect_equal(output$value, "orange")

})

})

#> Test passed with 2 successes 🎉.That doesn’t check that other is automatically selected when we start typing in the other box.

We can’t test that using testServer() because it relies on updateRadioButtons():

test_that("returns other value when primary is other", {

testServer(server, {

session$setInputs(fruit = "apple", other = "orange")

expect_equal(output$value, "orange")

})

})

#> ── Failure: returns other value when primary is other ───────────────────────────

#> Expected `output$value` to equal "orange".

#> Differences:

#> `actual`: "apple"

#> `expected`: "orange"

#>

#> Backtrace:

#> ▆

#> 1. ├─shiny::testServer(...)

#> 2. │ ├─shiny:::withMockContext(...)

#> 3. │ │ ├─shiny::isolate(...)

#> 4. │ │ │ ├─shiny::..stacktraceoff..(...)

#> 5. │ │ │ └─ctx$run(...)

#> 6. │ │ │ ├─promises::with_promise_domain(...)

#> 7. │ │ │ │ └─domain$wrapSync(expr)

#> 8. │ │ │ ├─shiny::withReactiveDomain(...)

#> 9. │ │ │ │ └─promises::with_promise_domain(...)

#> 10. │ │ │ │ └─domain$wrapSync(expr)

#> 11. │ │ │ │ └─base::force(expr)

#> 12. │ │ │ ├─shiny:::with_otel_span_context(...)

#> 13. │ │ │ │ └─base::force(expr)

#> 14. │ │ │ ├─shiny::captureStackTraces(...)

#> 15. │ │ │ │ └─promises::with_promise_domain(...)

#> 16. │ │ │ │ └─domain$wrapSync(expr)

#> 17. │ │ │ │ └─base::withCallingHandlers(expr, error = doCaptureStack)

#> 18. │ │ │ └─env$runWith(self, func)

#> 19. │ │ │ └─shiny (local) contextFunc()

#> 20. │ │ │ └─shiny::..stacktraceon..(expr)

#> 21. │ │ ├─shiny::withReactiveDomain(...)

#> 22. │ │ │ └─promises::with_promise_domain(...)

#> 23. │ │ │ └─domain$wrapSync(expr)

#> 24. │ │ │ └─base::force(expr)

#> 25. │ │ └─withr::with_options(...)

#> 26. │ │ └─base::force(code)

#> 27. │ └─rlang::eval_tidy(quosure, mask, rlang::caller_env())

#> 28. └─testthat::expect_equal(output$value, "orange")

#> Error:

#> ! Test failed with 1 failure and 0 successes.So now we need to use ShinyDriver:

test_that("automatically switches to other", {

app <- ShinyDriver$new(shinyApp(ui, server))

app$setInputs(other = "orange")

expect_equal(app$getValue("fruit"), "other")

expect_equal(app$getValue("value"), "orange")

})Generally, you are best off using testServer() as much as possible, and only using ShinyDriver for the bits that need a real browser.

21.5 Testing visuals

What about components like plots or HTML widgets where it’s difficult to describe the correct appearance using code?

You can use the final, richest, and most fragile testing technique: save a screenshot of the affected component.

This combines screenshotting from shinytest with whole-file snapshotting from testthat.

It works similarly to the snapshotting described in Section 21.1.4 but instead of saving text into an .md file, it creates a .png file.

This is also means that there’s no way see the differences on the console, so you’ll instead be prompted to run testthat::snapshot_review() which uses a Shiny app to visualise the differences.

The primary downside of testing using screenshots is that even the tiniest of changes requires a human confirm that it’s OK. This is a problem because it’s hard to get different computers to generate pixel-reproducible screenshots. Differences in operating system, browser version, and even font versions, can lead to screenshots that look the same to a human, but are very slightly different. This generally means that visual tests are best run by one person on their local computer, and it’s generally not worthwhile to run them in a continuous integration tool. It is possible to work around these issues, but it’s considerable challenge and beyond the scope of this book.

Screenshotting individual elements in shinytest and whole file snapshotting in testthat are both very new features, and it’s still not clear to us what the ideal interface is. So for, now you’ll need to string the pieces together yourself, using code like:

path <- tempfile()

app <- ShinyDriver$new(shinyApp(ui, server))

# Save screenshot to temporary file

app$takeScreenshot(path, "plot")

#

expect_snapshot_file(path, "plot-init.png")

app$setValue(x = 2)

app$takeScreenshot(path, "plot")

expect_snapshot_file(path, "plot-update.png")The second argument to expect_snapshot_file() gives the file name that the image will be saved in file snapshot directory.

If these tests are in a file called test-app.R then these two file snapshot will be saved in tests/testthat/_snaps/app/plot-init.png and tests/testthat/_snaps/app/plot-update.png.

You want to keep the names of these files short, but evocative enough to remind you what you’re testing if something goes wrong.

21.6 Philosophy

This document has focussed mostly on the mechanics of testing, which are most important when you get started with testing. But you’ll soon get the mechanics under your belt and your questions will become more structural and philosophical.

I think it’s useful to think about false positives and false negatives: it’s possible to write tests that don’t fail when they should, and do fail when they shouldn’t. I think when you start testing your biggest struggles are with false positives: how do you make sure your tests are actually catching bad behaviour. But I think you move past this fairly quickly.

21.6.1 When should you write tests?

When should you write tests? There are three basic options

Before you write the code. This is a style of code called test driven development, and if you know exactly how a function should behave, it makes sense to capture that knowledge as code before you start writing the implementation.

-

After you write the code. While writing code you’ll often build up a mental to-do list of worries about your code. After you’ve written the function, turn these into tests so that you can be confident that the function works the way that you expect.

When you start writing tests, beware writing them too soon. If your function is still actively evolving, keeping your tests up to date with all the changes is going to feel frustrating. That may indicate you need to wait a little longer.

When you find a bug. Whenever you find a bug, it’s good practice to turn it into an automated test case. This has two advantages. Firstly, to make a good test case, you’ll need to relentlessly simplify the problem until you have a very minimal reprex that you can include in a test. Secondly, you’ll make sure that the bug never comes back again!

21.7 Summary

This chapter has showed you how to organise your app into a package so that you can take advantage of the powerful tools provided by the testthat package. If you’ve never made a package before, this can seem overwhelming, but as you’ve seen, a package is just a simple set of conventions that you can readily adapt for a Shiny app. This requires a little up front work, but unlocks a big payoff: the ability to automate tests radically increases your ability to write complex apps.